مفتی اعظم بیتالمقدس

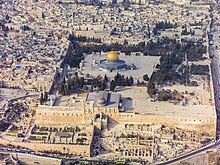

مفتی اعظم بیتالمقدس یا مفتی اعظم قدس، روحانی مسلمان سنی است که مسئول اماکن مقدس اسلامی بیتالمقدس از جمله الاقصی است.[۱] این جایگاه توسط دولت نظامی بریتانیا به رهبری رونالد استورز در سال ۱۹۱۸ تأسیس شد.[۲][۳] محمد احمد حسین از سال ۲۰۰۶، این سمت را به انتصاب رئیسجمهور فلسطین، محمود عباس، اداره میکند.

تاریخ[ویرایش]

قیمومیت بریتانیا[ویرایش]

مفتی اعظم جایگاهی بود که توسط مقامات قیمومیت بریتانیا ایجاد شد.[۲] این عنوان جدید را انگلیسیها برای «ارتقای وضعیت اداری» در نظر گرفته بودند.[۴]

هنگامی که کمیل الحسینی در سال ۱۹۲۱ درگذشت، کمیسر عالی بریتانیا، هربرت ساموئل، محمد امین الحسینی را به این سمت منصوب کرد. امین الحسینی، یکی از اعضای خانواده الحسینی بیتالمقدس، یک رهبر ملیگرا و مسلمان عرب در قیمومیت بریتانیا بر فلسطین بود. الحسینی به عنوان مفتی اعظم و رهبر کمیته عالی عرب، به ویژه در دوران جنگ ۴۵–۱۹۳۸، نقش کلیدی در مخالفت خشونتآمیز با صهیونیسم ایفا کرد و از نزدیک با رژیم نازی در آلمان متحد شد.[۵][۶]

وقف اردن[ویرایش]

در سال ۱۹۴۸، پس از اشغال بیتالمقدس توسط اردن، عبدالله اول اردن رسماً الحسینی را از سمت خود برکنار کرد، او را از ورود به بیتالمقدس منع کرد و حسامالدین جارالله را به عنوان مفتی اعظم منصوب کرد. با مرگ جارالله در سال ۱۹۵۲، وقف اسلامی بیتالمقدس اردن سعد العالمی را به عنوان جانشین وی منصوب کرد.[۷] وقف در سال ۱۹۹۳ پس از مرگ العالمی، سلیمان جعبری منصوب کرد.[۸]

تشکیلات خودگردان فلسطین[ویرایش]

پس از مرگ جعبری در سال ۱۹۹۴، دو مفتی رقیب منصوب شدند: تشکیلات خودگردان فلسطین، اکریمه سعید صبری را نامزد کرد، در حالی که اردن عبدالقادر عبدین را رئیس دادگاه تجدید نظر مذهبی معرفی کرد.[۹][۱۰] این منعکس کننده تناقض میان پیمان اسلو یکم بود که انتقال قدرت از اسرائیل به تشکیلات خودگردان را پیشبینی میکرد و معاهده صلح اسرائیل و اردن که سرپرستی اماکن مقدس بیتالمقدس را به رسمیت میشناخت.[۱۱] مسلمانان محلی دیدگاه سازمان آزادیبخش فلسطین را مبنی بر اینکه اقدام اردن یک مداخله ناموجه بود، تأیید کردند.

صبری در سال ۲۰۰۶ توسط محمود عباس رئیس تشکیلات خودگردان، که بابت اینکه صبری بیش از حد درگیر مسائل سیاسی بود نگرانی داشت، برکنار شد.[۱۲]

عباس محمد احمد حسین را منصوب کرد که به عنوان یک میانهرو سیاسی شناخته میشد. مدت کوتاهی پس از انتصاب، حسین اظهاراتی را بیان کرد که نشان میدهد بمبگذاری انتحاری تاکتیک قابل قبولی برای فلسطینیها برای استفاده علیه اسرائیل بود.[۱۲]

فهرست کنید[ویرایش]

- کمیل الحسینی از زمان خلق این نقش در سال ۱۹۱۸ تا زمان مرگش در سال ۱۹۲۱م.

- محمد امین الحسینی از ۸ مه ۱۹۲۱ تا ۱۹۴۸; در سال ۱۹۳۷ توسط بریتانیا تبعید شد اما از سِمت مفتی عزل نشد[۱۳][۱۴]

- حسام الدین جارالله از ۲۰ دسامبر ۱۹۴۸ تا ۶ مارس ۱۹۵۴[۱۵]

- سعد العلمی از ۱۹۵۳ تا ۶ فوریه 1993[۱۶][۱۷]

- سلیمان جعبری از ۱۷ فوریه ۱۹۹۳ (اردن) / ۲۰ مارس ۱۹۹۳(از سوی تشکیلات خودگردان) تا ۱۱ اکتبر ۱۹۹۴[۱۸]

- عبدالقادر عبدین (اردن) از ۱۱ اکتبر ۱۹۹۴ تا ۱۹۹۸[۱۹]

- اکریمه سعید صبری (PA) از ۱۶ اکتبر ۱۹۹۴ تا ژوئیه ۲۰۰۶ [۱۹]

- محمد احمد حسین از ژوئیه ۲۰۰۶ تا کنون

جستارهای وابسته[ویرایش]

استناد[ویرایش]

- ↑ Friedman, Robert I. (2001-12-06). "And Darkness Covered the Land". The Nation. Archived from the original on 2007-11-18. Retrieved 2007-09-13.

- ↑ ۲٫۰ ۲٫۱ See Islamic Leadership in Jerusalem for further details

- ↑ The terminology was used as early as 1918. For example: Taysīr Jabārah (1985). Palestinian Leader Hajj Amin Al-Husayni: Mufti of Jerusalem. Kingston Press. ISBN 978-0-940670-10-5. states that Storrs wrote on November 19, 1918 "the Muslim element requested the Grand Mufti to have the name of the Sharif of Mecca mentioned in the Friday prayers as Caliph"

- ↑ The Encyclopaedia of Islam, New Edition: Supplement. Brill Archive. 1 January 1980. p. 68. ISBN 90-04-06167-3.

- ↑ Pappe, Ilan (2002) 'The Rise and Fall of a Palestinian Dynasty. The Husaynis 1700-1948. AL Saqi edition 2010. شابک ۹۷۸−۰−۸۶۳۵۶−۴۶۰−۴. pp.309, 321

- ↑ Cohen, Aharon (1970) Israel and the Arab World. W.H. Allen. شابک ۰−۴۹۱−۰۰۰۰۳−۰. p.312

- ↑ "Obituary: Saad al-Alami". The Independent. February 10, 1993.

- ↑ Blum, Yehuda Z. (1994). "From Camp David to Oslo". Israel Law Review. 28 (2–3): note 20. doi:10.1017/S0021223700011638. S2CID 147907987.

the Mufti of Jerusalem died in the summer of 1994 and the Government of Jordan appointed his successor (as it had done since 1948, including the period since 1967)

[reprinted in Blum, Yehuda Zvi (2016). Will "justice" bring peace?: international law-selected articles and legal opinions. Leiden: Brill. pp. 243–265. doi:10.1163/9789004233959_016. ISBN 9789004233959.] - ↑ Rowley, Storer H. Storer (6 November 1994). "Now Muslims Argue Over Jerusalem". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 2 October 2021.; Ghazali, Said (6 March 1995). "Activist Mufti Sees Himself as Warrior for Jerusalem". Associated Press. Retrieved 2 October 2021.

- ↑

{{cite book}}: Empty citation (help) - ↑ Wasserstein, Bernard (2008). "The battle of the muftis". Divided Jerusalem: the struggle for the holy city. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. pp. 338–341. ISBN 978-0-300-13763-7 – via Internet Archive.

- ↑ ۱۲٫۰ ۱۲٫۱ Yaniv Berman, "Top Palestinian Muslim Cleric Okays Suicide Bombings", Media Line, 23 October 2006.

- ↑ An answer in the Commons to a question on notice, given by the Secretary of State for the Colonies:

Mr. Hammersley asked the Secretary of State for the Colonies why no appointment has yet been made to fill the posts of Mufti of Jerusalem and President of the Moslem Supreme Council?

Colonel Stanley. An important distinction must be drawn between the two offices referred to by my hon. Friend. The post of Mufti of Jerusalem is a purely religious office with no powers or administrative functions, and was held by Haj Amin before he was given the secular appointment of President of the Supreme Moslem Council. In 1937 Haj Amin was deprived of his secular appointment and administrative functions, but no action was taken regarding the religious office of Mufti, as no legal machinery in fact exists for the formal deposition of the holder, nor is there any known precedent for such deposition. Haj Amin is thus technically still Mufti of Jerusalem, but the fact that there is no intention of allowing Haj Amin, who has openly joined the enemy, to return to Palestine in any circumstances clearly reduces the importance of the technical point. - ↑ Zvi Elpeleg's "The Grand Mufti", page 48: "officially he now retained only the title of Mufti (following the Ottoman practice, this had been granted for life)"

- ↑ Nazzal 1997 p. xxiii

- ↑ Nazzal 1997 p. 34

- ↑ "Saad al-Alami Dead; Jerusalem Cleric, 82". The New York Times. 1993-02-07. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2015-10-22.

- ↑ Nazzal 1997 xlix, p. 110

- ↑ ۱۹٫۰ ۱۹٫۱ Nazzal 1997 p. lvii